It’s axiomatic to say that occupation is intimately tied to place. While telecommunications have theoretically liberated many fields from their locations, still, to be a fisherman, one needs water.

Boat images on tombstones, of course, are not limited to working boats, and pleasure boats are harder to geographically pinpoint than commercial craft. You may need water for sport boats, but you don’t need much. Commercial fishing requires big water. While some commercial fishing does obtain in fresh water, the vast bulk of it draws from salt water. In the Oregon Territory there is one great fishery not located in the ocean, that of the Columbia River; and while they catch a variety of fish in this mighty river, the bulk of the catch is salmon of one form or another; and the most efficient way to fish salmon in the river is via gill nets. Gill nets, as the name suggests, catch fish by entangling their gills in a net. Nets are designed of specific dimensions to catch only a certain size fish, while letting the rest escape, and at that they’re fairly effective.

(A word here on spelling: A boat that employs a gill net — or a gill-net, as the case may be — is known as a gill netter, a gill-netter, or a gillnetter. There seems to be no standard, even within a given publication.)

Gill-netting is an ancient technique probably predating our diaspora from Africa. It’s probably not coincidence that all hominin finds were originally laid down in moist conditions, with the only notable exception being a double set of footprints found in a then-fresh volcanic deposit. And it’s probably not coincidence that the diaspora appears to have been made via the shore of the Indian Ocean at such a speed and over such large aquatic distances that boats are a much better explanation than whole families swimming or being blown along on log jams. There’s probably a reason that invasions of new territory happened along river channels and not savannas or woodlands. There’s a reason why it’s now being considered that shell tools may have predated stone ones. There is a reason why people are known as the “beach monkey.” For that matter, we still all live at the beach, with our running water, and all.

In any event, The knot was undoubtedly one of the first serious human inventions/understandings that allowed us to explode as a species, as not only did it allow us to make clothes and fashion weapons so that we could finally extend our range off the confines of the beach, but it led, probably quite quickly, to making nets of all kinds; and it wouldn’t have taken too much fishing with nets to find out which size mesh worked best for which fish. Unfortunately, any materials used in making any but the most recent nets have long since vanished, so it’s currently impossible to date the origins of gill-netting, but suffice it to say it goes back a long, long way.

It’s most likely that gill nets were first employed along streams and estuaries without the assistance of boats, where they are still used by both commercial and indigenous fishermen. The advent of suitable craft allowed the fisherfolk to extend their trade into bigger and bigger waters, including the Columbia.

The early post-invasion gill-netters on the Columbia were a colorful lot. Rowed to the fishing grounds and either powered or stabilized by sails, pictures of them show what looks like a flotilla of butterflies floating on the river surface. The current crop of motorized netters isn’t nearly as picturesque, but the more common style of Columbia River gill-netter, the bowpicker, is still a distinctive enough vessel and one that shows up on headstones much more often than the generally larger sternpicker.

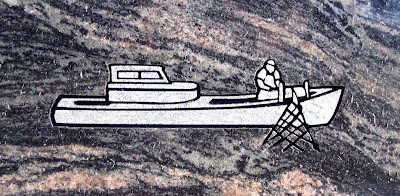

The names describe how the net is pulled aboard the boat; and seeing as one has to be dragging a net towards them while reeling it in, it behooves the boat to be moving away from the net during the operation, which mean a bowpicker reels in the net while puttering backwards. Putting the net up front also lends the boat a distinctive appearance by moving the wheelhouse to the back rather than its more usual forward position.

The Columbia gill-netters are generally small boats operated by one or two persons. At this point in time they are essentially an overlooked throwback, a once enormous industry now marginalized and whose greatest service to society is no longer the production of food but the retention of folkways. The headstone carvings shown here represent — can we say it? — a dying breed. They’re part of what makes life on the Columbia different from life on, say, the Mississippi (after all these years I can still remember how to spell that word). Similar boats, of course, are found over the entire world, but not uniformly distributed. Here they’re a beloved nuance of the Oregon Territory mostly restricted to the Columbia.

I may have missed a boat or two from my collection, and my collection holds photos of by no means all the boat carvings on headstones in the Territory, but the eight here are certainly a good selection of what’s available. They all emanate from cemeteries close to the river. And just by looking at them, I’d venture that six (I actually have one more that couldn't be downloaded) of the eight were fashioned by the same artist. Only the stained-glass representation in Cathlamet and the boat riding on a stylized sea of pointy waves from Ocean View look as if they’re done by other people. The remaining six look suspiciously alike. And, without being too harsh an art critic, the remaining six are intimidatingly simplistic in their execution. Notably so in an industry that generally does very fine work. It’s as if a folk artist snuck in for this tiny niche.

What’s particularly nice, though, about this artist’s series of engravings is that, considered as a whole, they illustrate some of the high points of the job. Two of them show nets in the water; one of which shows the direction the boat is moving vis-à-vis the net, while the other shows a person working the net. Another shows a stabilizing sail unfurled, and another has two people sitting in the stern.

I might point out that the boat riding the stylized waves displays Washington State registration numbers, although the cemetery is in Oregon. It and the stained-glass memorial (the only depiction of the boats from a frontal view) reflect the generally higher industry standards of design; nonetheless, this artist’s contribution to the local headstone scene is significant and worth keeping ones eye out for. And I should note that this industry concentrates in the lower reaches of the Columbia, just before it enters the Pacific. The netters have never reached as far inland as Portland.

No comments:

Post a Comment