|

| Agency Mission Cemetery |

JFK was our first minority president. It’s hard to picture that wavy-haired youth, stylish First Lady, Camelot and all, being our first minority President, but he was: Catholic. It’s hard to picture Catholics as a minority. Isn’t the Pope Catholic? Don’t they have all of South America? How can they be a minority?

|

| Chief Schonchin Cemetery |

Nonetheless, during his campaign it was a mighty issue and one that threatened to derail him, much as Obama’s milk chocolate skin. The 2012 elections showed how much the demographics of the country have changed in the ensuing half-century since Kennedy. Now, all those little minorities have morphed into one majority. Suddenly, a putative black man represents the face of America today. The WASP days are definitely on the wane. Adios and good riddance.

|

| Agency Cemetery |

Catholic? Black? We almost had a Mormon, funny underwear and all. So when will there be a Jewish President, already? Heck, the way the country is going, we’ll soon have a gay Latina running the place. Let’s see her bomb Afghanistan. Asian? Why not?

Anybody but an Indian. You can’t be President if you’re from another nation. Sorry, guys, it’s the way they wrote the laws; you wanna be President, you have to be a Native-American, not a Chippewa, or a Paiute, or a Mohican. You have to be a plain old anybody from Anywhere, USA.

|

| Indian Cemetery - Husum |

Not that one couldn’t be born on a reservation and become President of the United States, that’s perfectly legal (I think). What one can’t do is spend one’s life fighting for status as a sovereign nation and then want to be President of ours. I don’t think the rest of us minorities (hey, I’m a minority now) are going to want to vote for someone who’s perennially pissed off at us.

|

| Agency Cemetery |

Jesus, how did that happen? How come one minority is shut out of the game? Oh sure, it’s PC to idolize the Indians, these days; but when it comes to having them do anything for us besides building casinos and being a tourist attraction, they are—I’m going to say this—low on the totem pole. And for sure, it’s not their fault. In fact, it’s no one’s fault; it’s just the way history rolled out: sometimes you’re the victor, sometimes you’re the loser. Happens to us all.

|

| Paiute II Cemetery |

What doesn’t always happen is that the losers don’t always get shunted away onto reservations which are mythical sovereign nations. They are, of course, nothing like nations (built on unemployment, casinos, and alcohol) much less sovereign, but it’s a comfortable fiction for both sides. Unfortunately, rather than giving the Indians independence, respectability, and a place among the nations of the world, we gave them a ghetto thousands of acres broad. It couldn’t be helped. It was a product of the times. A couple hundred years earlier and the Indians would have simply melted into the rest of the population. Setting them aside on barren tracks of land and giving them the illusion of independence has kept them from successfully joining the mainstream. Of course, the Indians don’t want to join the mainstream, but that’s pride talking, not wisdom.

|

| Chief Schonchin Cemetery |

The result is they’re stuck on reservations set aside from the rest of the country, and because of those reservations, will never be able to fully join the body Americana. The curse of an inappropriate gift. They are welded to the memory of a dream-time long since vanished under the wagon wheels of settlers. It is, alas, one more legacy of farming. Farmers grow many people and big armies and they always need more land. No tribal society can withstand the march of the plow. It’s a story 10,000 years in the making.

|

| Paul Washington Cemetery |

It makes for an uncomfortable truce. Reservations have quasi autonomy, and the lack of true autonomy creates a never ending undercurrent of tension between people from the rez and those from beyond. Us. There is, as far as I can tell, no solution. The pattern is set; the lines are clearly drawn; there’s no going back. No one’s about to give up their reservation and government support. It’s all they have left. Except, of course, for their pride. (If I were them, I’d concentrate on building community colleges instead of casinos, but what do I know?) Likewise, you can be sure the farmers aren’t going to give up their land. Or their government support.

|

| Paul Washington Cemetery |

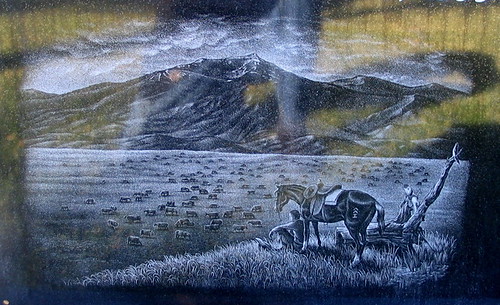

Indian graveyards don’t have to be on reservation land to have an unworldly feel to them. Given, each graveyard is different from any other graveyard just as any human is different from any other human, but upon entering an Indian graveyard one immediately knows they’re in a place apart from the common. In those carefully crafted windows onto a community’s soul, an alien gestalt wraps around the mounds covering the dead. This is not your farmer’s graveyard.

|

| St. Andrews Cemetery |

The emotions surrounding an Indian cemetery are complex and strong. How they feel about them and how they feel about outsiders visiting them is writ in the “no trespassing” signs one sees at many of them. There are other gated and locked cemeteries out there, but they’re rare. By far, most cemeteries are open to whomever happens by; nice for visitors and vandals alike. Part of the problem with visitors to Indian cemeteries is that the cemeteries have suffered an inordinate amount of vandalism through the years, much of it sanctioned for and paid for by prestigious American universities and museums. Americans went through Indian graveyards like the British through Greece, stealing everything they could get their hands on. The Americans, though, weren’t content with just grave goods; they went so far as to steal whole bodies; skulls, if nothing else.

|

| Agency Mission Cemetery |

Casting one blanket over all the Indian tribes, of course, doesn’t do justice to the diversity of cultures found in a land as varied as the Oregon Territory. Coastal tribes lived a significantly different lifestyle than did those from the interior. Nez Perce were distinct from the Paiute. Each had its own culture and nuances, and each treated their dead in a different manner; distinctions which had to be submerged in the move to reservations that combined tribes, not only quite different from each other, but sometime mortal enemies. Life in pre-American Oregon Territory was no Rousseauian idyll. There may not have been many Indians left after diseases ravaged their peoples, but for those who were left, peace settled over the land like snow. One could finally walk the breadth of the Territory without fear of being killed. Nonetheless, it’s only fair to warn you, being an outsider in an Indian cemetery can cause trouble. Inadvertent as it may be, your very presence can be an irritant; and many Indians are disturbed that outsiders would want to visit their cemeteries, much less take pictures of them. I once stirred up a hornet’s nest by innocently asking a tribal historian if there was someone who could talk to me about the changes in burial practices that they’ve gone through since the arrival of the Americans. They were outraged to find I’d been taking pictures of their cemetery, not to mention writing about them. This very article will, undoubtedly, put some of them on edge. The general gist was that no one should talk about or write about Indians without being an expert and preferably Indian. Sort of like one shouldn’t write about highways without being a traffic engineer.

Okay, so shoot me.

|

| Agency Cemetery |

Beyond that, though, Indian cemeteries are interesting for the large amount of personal items that tend to be left at graves. Grave site decoration is becoming more and more prevalent in the U.S., despite the sextons’ eternal battles to maintain the place; but rarely is it encouraged to bloom the way it does at Indian cemeteries. They can be bewildering. The first one I experienced—one that my wife and I happened to stumbled upon at the side of a highway—we had to spend some time looking at to even decide that it was a cemetery; our first impression was confusion because it seemed like no place for a junk yard, yet there was a staggering variety of things strewn about. Finally, clues here and there led us to understand the nature of the place.

|

| Paiute II Cemetery |

I believe I was wrong about my first impressions, which included the idea that this small cemetery alongside the road represented the disintegration of Indian culture in the face of the onslaught. I no longer think that. If the historian had taken the time to talk to me, I’d probably have understood it sooner. What it represents, I’ve gathered from further reading and observation, is the continuation of age-old traditions with an overlay of American-Christian practices. Indian cemeteries before the appearance of the white man were equally strewn with grave objects, personal items of the deceased. One of the reasons for the enmity between the Indians and the invaders is that the invaders saw the cemeteries as ripe for the picking. For a long time, it had been custom among many tribes to put the deceased in canoes; but after the arrival of the Americans they had to start smashing holes in the bottoms of the canoes so they wouldn’t be stolen. It’s easy to see why they’re reluctant to have Americans in their cemeteries.

|

| Old Agency Cemetery |

The Indians who railed against me never seemed to understand that I shoot cemeteries. All and every cemetery. The proportion of Indian cemeteries in my portfolio is minuscule. I wasn’t emphasizing them or zoning in on them. I wasn’t elevating them or demeaning them; I was just showing their cemeteries along with everybody else’s. Still am. I’m sorry they got pissed, but I figure it’s their problem. I gotta keep doing what I gotta do; they gotta keep doing what they gotta do.

|

| Paul Washington Cemetery |

It’s a cautionary tale for those of you who might be inspired to search out Indian cemeteries in your area. Like all cemeteries, they’re endlessly fascinating and some of the more colorful graveyards around. It would be nice if someone would shoot the different styles from around the country, but it would be a touchy subject. It’s not a job for an outsider.

|

| Indian Cemetery - Husum |